Guide to giving for new PHILANTHROPISTS/social investors

PHILANTHROPIC GIVING AND SOCIAL INVESTMENT - A FULFILLING PERSONAL JOURNEY; MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Wealthy individuals and their families are increasingly looking for opportunities to engage responsibly in order to make a difference. The opportunity to do this is broad, ranging from pure charitable giving to professional social or impact investing, and the journey can be very rewarding and fulfilling. The personal value proposition leads the decision-making process in choosing a suitable pathway.

There are typically three main approaches:

- Pure philanthropic engagement – donating funds and not expecting a financial return;

- Venture philanthropy – seeking to maximise some form of societal return and engaging your time and energy in a social venture; or

- Intentional/social investment strategy – focused primarily on social enterprise and seeking to maximise societal return while receiving some financial return.

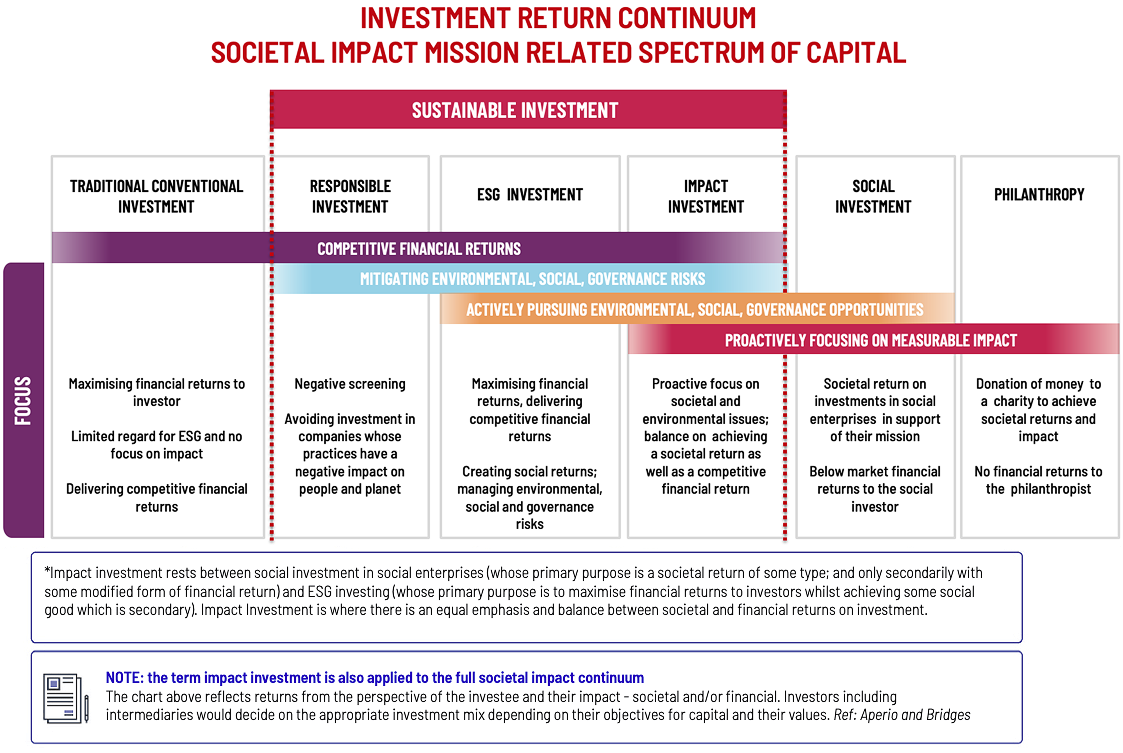

An additional approach to complement these is sustainable and impact investing, whereby an investor seeks to maximise their financial return as well as a societal or environmental return. The engagement or investment in these different ways is often value driven. People are motivated by their ambitions to do something beneficial for society or the environment based on their own values. A clear vision gives purpose and direction when embarking on this rewarding endeavour.

Crypto for Good is a growing area:

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/magazine/philanthropy-impact-magazine-issue-33-part-1-of-2/

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/magazine/philanthropy-impact-magazine-winter-edition-33-part-2-of-2/

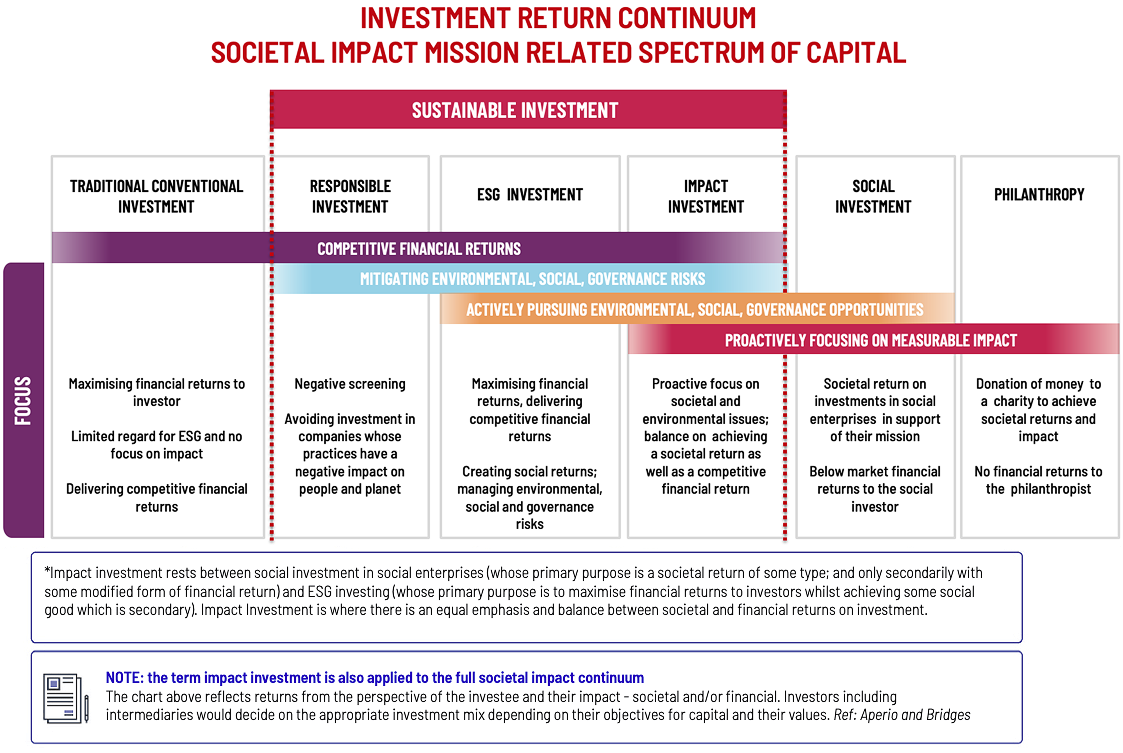

See Investment Return Continuum. The continuum is a context within which philanthropists and ESG/impact investors can understand the various approaches to sustainable investment.

See list of episodes of Walk in my Shoes webinar series with topics such as: Understanding your Client Needs, Digital and technology, Donor Advised Funds, Global Trends, Systemic Change, Impact Investing, Cause Specific, Social Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation, Social Equity, Women of Wealth - Next Gen and Wealth Transfer, COVID-19

Pure Philanthropic Engagement

Some questions to ask yourself to get started could be:

- Have you already identified causes/what you want to support, or do you have no idea what you want to achieve?

- Are there family challenges you have faced and/or have your friends been through things that have seriously affected them?

- Are there articles in the news, either domestically or internationally, that concern you?

- Do you know which of your assets you are ready to give – is it purely financial or do you have other resources that could be of value to others?

- How long do you want to do this for?

- Do you want to do this on your own or collaborate with others?

Note, these questions do not need to be answered in this order. Identify which ones you already know the answer to, and shape your answers to the others around that.

The goal is to define your objectives, and then how you can action them and reach those goals.

Rockefeller Advisory Services’ Philanthropy Roadmap provides an excellent overview of how to plan your giving. They released a very detailed report, Reimagined Philanthropy: A Roadmap to More Just World about the questions and reflections that emerging philanthropists should consider.

There are also eight other questions that philanthropists should consider: Are you cognisant of the inequalities our philanthropic systems are built on?

- Are your short-term gains laced with long-term harms?

- Are communities being empowered to determine their own solutions?

- Have you done the work or are you taking shortcuts?

- Are you engaging with the grassroots and valuing them properly?

- Do those on your board reflect the communities you are serving?

- Is your philanthropy truly catalytic?

- In whose name is this being done?

LGT and Philanthropy Insight’s report provides a very useful framework to take donors through every stage of their journey.

If you are only just getting started and it is important to you that you fund topical projects that have urgent need, UBS’ Top Five Trends in Philanthropy 2023 and 2025 is a valuable holistic vision of the current state of philanthropy sector.

A lot of donors choose for their donations to be restricted grants, which often need to be assessed and reported on and the charities need to demonstrate the funds have only been spent on an agreed project. Many do not like their grants to cover core costs but over the last few years, that mindset has been increasingly challenged. In his Ted Talk, Dan Pallotta presents a useful summary of why that is.

Darren Walker, President of the Ford Foundation and ex-Vice President at the Rockefeller Foundation released an insightful book in 2023, From Generosity to Justice: A New Gospel of Wealth. It reflects back on the vision of Andrew Carnegie, and how it relates to modern times.

There are also groups of philanthropists who come together to learn from their peers and develop, or improve their practice. Forward Global (previously named The Philanthropy Workshop), Toniic and the Global Impact Investing Network are the most well-known and for those that are inheriting their wealth and are concerned about where it came from, the Good Ancestor Movement is a group of that has been formed to help bring them together.

One approach that not many people take is educating young children about philanthropy. If you have young children who will be inheriting your wealth, it is useful to understand how children can be taught about giving, and also how the material they use can help, or hinder this approach. The Giving Machine and the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy also offer useful advice on this topic.

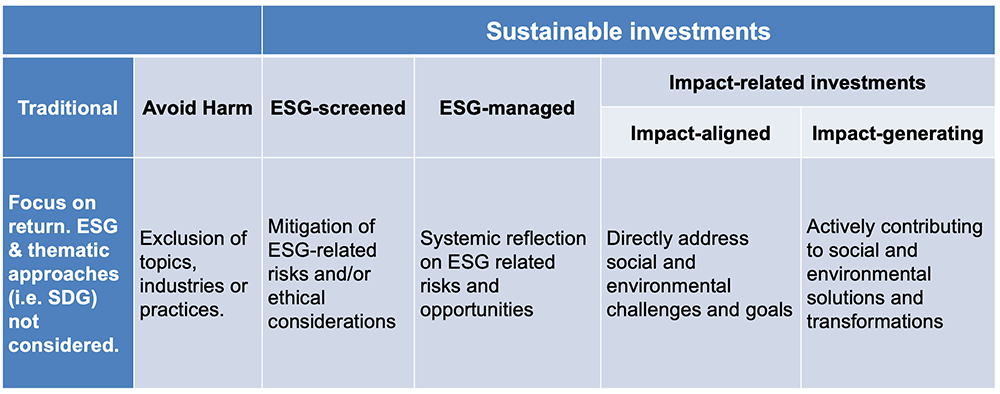

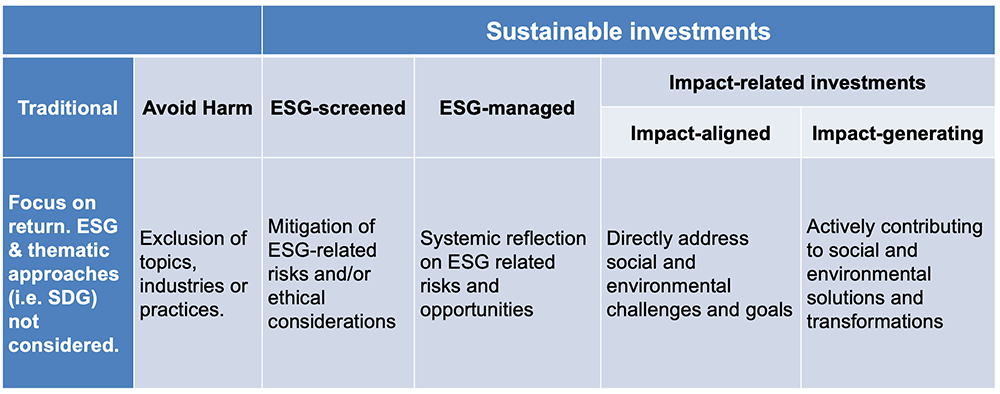

Your Total Portfolio Impact

It is important to get a broad sense of what your investment portfolio looks like; where and how your assets are invested, and whether this aligns with your values; and what you would like to achieve with your wealth. By looking at the table below, you can get an understanding of the spectrum of capital impact from traditionally managed investments all the way through to philanthropic funding. (Philanthropy Impact Spectrum).

Individuals, foundations and families alike are increasingly moving towards considering a “total portfolio impact approach”, which means aligning your investment portfolio with your values and your philanthropy. This strategic approach creates maximum positive impact and ensures investments do not cause harm. For example, it will ensure you do not invest in tobacco and alcohol at the same time as supporting cancer charities. This is an increasingly important consideration for Gen Z, Millennials and and women of wealth, who want to authentically engage with societal issues and address them through all channels.

With the growing awareness around ESG/impact and responsible investments, this is now easier to achieve. Your wealth managers and professional advisors are more likely to ask you early on, and when reviewing your investment criteria, if you wish for your portfolio to comprise responsible investments aligned with your values.

There are also more accessible “impact investments” being offered by asset managers, which can align with your philanthropic mission – and it might be worth considering such funds, which are often thematic, addressing areas such as health and wellbeing, biodiversity and clean energy.

If you really wish to have all your assets working towards your goals, you should take steps to work with your professional advisors to achieve this.

See Typology of Sustainable Investments below, which describes investments from traditional to impact-generating, with some key characteristics.

Typology of Sustainable Investments - Strategic Purpose of the Investment

SPECTRUM OF CAPITAL INVESTMENT-RETURN CONTINUUM

While donating to a good cause or investing in a social enterprise may seem simple, a lot can go wrong, particularly when significant amounts are being invested. Sophisticated advice, knowledge and learning are therefore essential to your success. Support from professional advisors may be helpful if you are embarking on a donor and social investment journey or reviewing your current approach.

In summary:

a. Be aware of your motivation. The following points outline the variety of reasons why wealthy individuals get involved with philanthropy:

- Responsibility: having created wealth, they feel a responsibility to give back to the individuals and society that helped them on their way. They wish to align their values with their money.

- Family values: they come from a family that gives, or they want to demonstrate to their children the importance of empathising with those who are less fortunate.

- Peer group: they are part of a community (often religious) that gives, and they continue in that tradition.

- Life changing event: whether selling a company or coming to terms with a tragic event, life changing events often change the priorities of individuals. They may have more time on their hands and want a new challenge, or they may have very personal reasons for focusing on a particular cause.

- Legacy: it is a cliché that the first half of life is about success and the second half is about significance. However, for some wealthy donors, the desire to leave traces of a well-led life is a powerful motivator.

- Restructuring for wealth and estate planning: others leave gifts to charities for estate-planning purposes, or because they don’t have children to whom they can pass on their wealth.

b. Agree the causes or issues you would like to address, in order to live your values and motivations. Use a modified version of investigation as if it were a business proposition, including research, developing a vision, strategy, business planning and risk analysis/mitigation.

c. Establish the level of involvement you and/or your family would like to have and are capable of commiting to. Be aware there are several different approaches to philanthropic giving, some of which are:

Values-based philanthropy

- Donors prioritise their values to help effectively channel donations.

Strategic philanthropy – predictive model

- Decide a clear goal, and design and implement how to achieve it/impact; strategy-based on evidence/data-driven strategies.

Transformative Philanthropy

- Turns the power of money into creative and decision-making power for many; donors are part of the process in direct contact with the supported group.

Emergent philanthropy

- Motivation to pioneer and disrupt, innovate and to make a significant difference. The approach combines elements of venture philanthropy and the application of an emergent strategy.

- Emergent strategy accepts that a realised strategy emerges over time as the initial intentions collide with, and accommodates to, a changing reality. The term “emergent” implies that an organisation is learning what works in practice.

Catalytic philanthropy

- Catalyses/mobilises a campaign that achieves measurable impact; focuses on issues to resolve, not on organisations to support.

Venture Philanthropy

- High-engagement and long-term approach whereby an investor for impact supports a social purpose organisation (spo) to help it maximise its social impact – funding and expertise.

d. Establish as part of ones planning an approach to evaluation – evaluating the process of implementation and then the outcomes and impact.

See more detailed information on the seven stages of giving.

Pure philanthropic funding is often a catalyst for transformation and has an important role to play in supporting charities to make change happen.

Some donors want to give practical support to causes which are close to their heart, while others are more interested in influencing complex societal issues. Personal philanthropic engagement can be very innovative and satisfying, and is more strategic than charity, which is an immediate response to an acute issue or disaster. Private philanthropy often takes a more explorative approach in order to tackle burning issues. Success stories can then be scaled up efficiently and translated to similar causes.

The entry points are taking a business-like approach, being strategic and utilising common sense – together with a curious and explorative mind-set.

Resources:

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/philanthropy-impact-magazine-issue-29_autumn_2023.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/philanthropy-impact-magazine-issue-26-pt1_final.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pi_magazine_11_final.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pi_magazine_10_final.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pi_magazine_6_final.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pi_mag17_aw_final_all_pages.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pi_magazine_14_pgs_all_0.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pi_magazine_13_final.pdf

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pi_mag_19_final.pdf

The Benefits of Advisors:

Advisors: be proactive with clients about sustainable investing

by Jon Hale, May 22, 2019

What do clients really want from their wealth manager?

by Caroline Burkart, January 6, 2020

Why you need a philanthropy advisor on your team

by Emma Beston, PI Magazine, Spring 2018

Awakening the millennial philanthropists: a guide for professional advisors

by Lauren Janus, PI Magazine, Spring 2018

Philanthropy: What advisors need to know about the new age of philanthropic giving

by Sianne Haldane and James Maloney, PI Magazine, Summer 2020

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/magazine/issue-32-spring-2025-part-2-of-3/

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/magazine/issue-30-summer-2024-part-2-of-2/

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/magazine/issue-30-summer-2024-part-1-of-2/

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/magazine/issue-30-summer-2024-part-2-of-2/

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/magazine/?tab=latest-editions

Note: Philanthropy Impact would recommend getting advice from a regulated Tax Advisor before making a decision.

Additional to philanthropic giving and social investment, consider ESG/impact investing.

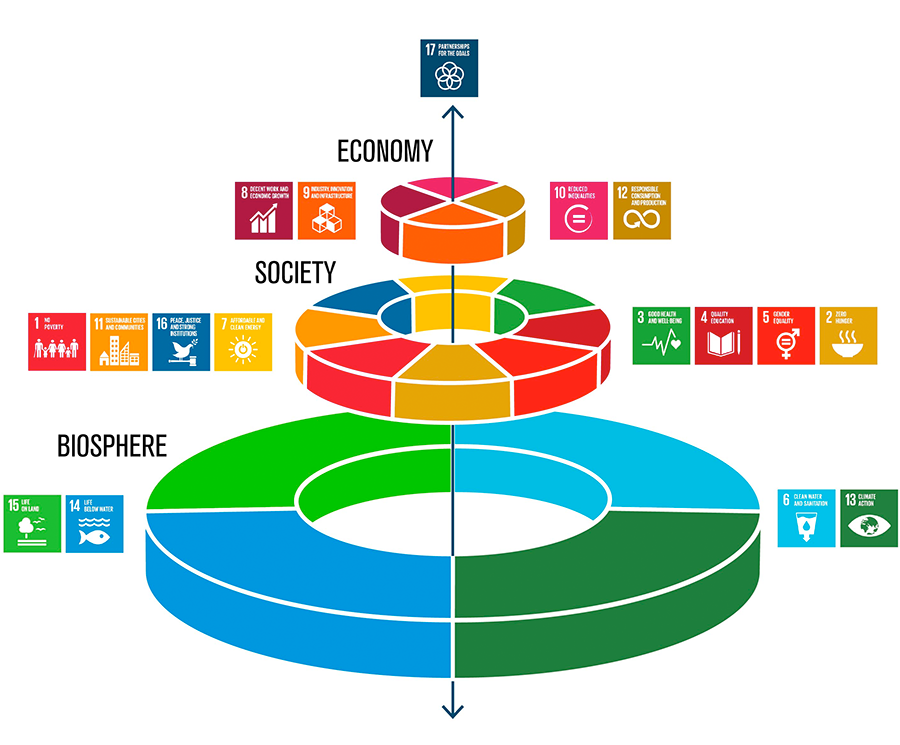

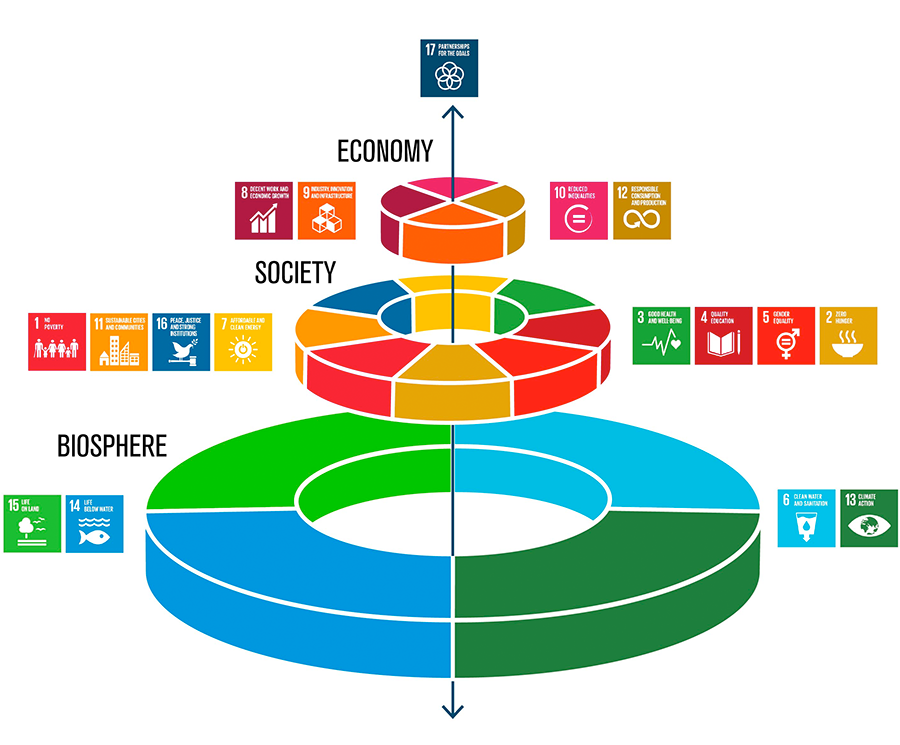

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the blueprint for achieving a better and more sustainable future for all, and provide a great framework with which to align your activities. Agreed by 193 countries in 2015, the 17 SDGs underpinned by 169 targets and 244 indicators, are the world’s ‘to do’ list for the next 10 years. The SDGs make it clear that the global community relies heavily on the private sector to solve some of the most urgent problems the world is facing. Both companies and institutional investors are being asked to contribute to the SDGs through their business activities, asset allocation and investment decisions.

Note: the SDGs are growing in importance as more ESG/impact investors and philanthropists are contextualising their activities within the SDGs.

These can be categorised into four impact & investment themes:

Failure to achieve the SDGs will impact all countries and sectors and create macro financial risks. Universal owners’ portfolios are inevitably exposed to these growing and widespread economic risks – which are in large part caused by the companies and other entities in which they are invested.

Another way of looking at the SDGs is through biosphere, society and economy. This leads to a better understanding of how they might be applied and how a philanthropist and social impact investor can use them to set priorities. See chart below.

In a previous edition of our magazine, entitled What Kind of Society Do We Want To Build? there were 42 articles; the authors, their colleagues and their organisations proactively designing and implementing a ‘new normal’ – very inspirational, indicating the future holds promise.

Part 1 of this edition, SDGs – Driving Societal Priorities: Leading to a Just Society, addresses the issue in a number of ways. The editorial states:

Andrew McCormack asks the question: can the world achieve sustainable development? He says: "The world has the appetite and capacity for sustainable development. It has less than a decade to show the collective determination it needs to achieve its common goals."

Other articles outline how the SDGs applied in ESG impact investing can support the changes needed to achieve the SDGs, applying suitability criteria to enable investors to live their values and achieve their ambitions. To this end, Greg Davies explores the behavioural implications of impact on everything from philanthropic giving to impact investing.

Michael Alberg-Seberich address SDGs from another perspective – the challenge of measuring impact. As he says: "The SDGs are not perfect, but they open the door to intense client conversations about impact. The effect of the SDGs on the corporate discourse on impact targets is an indication for this."

International examples are explored in a number of articles from Russia to Asia to India; including a case history of an international philanthropist who is part of the Maverick Collective. The latter, Stasia Obremskey sums it up: “My motto these days is ‘yes, And.’ YES philanthropy AND impact investing, to have more influence on women’s lives. Yes, invest locally AND globally as the needs are great in both markets. YES mission AND financial returns to drive more investment capital into women’s health. YES, education AND more and better products that enable women to manage their fertility, allowing them to make their mark on the world. The world so needs the minds and voices of women, working with men, to solve our most pressing problems—from climate change, economic inequities and disparities in health, education, and well-being. Let’s invest in improvements in reproductive health and education for women and girls to make the world a better place.”

This is not just the beginning. There is a worldwide movement in support of achieving the SDGs, a momentum leading to a just society.

Just watch this space… as SDGers in multiple environments on a never-ending road create a sustainable world with healthy and sustainable economies, societies and biosphere.

Driving Investment Strategy

Achieving the SDGs will be a key driver of global economic growth, which any long-term investor will acknowledge as the main ultimate structural source of financial return over the long term. Economic growth is the fundamental driver of the growth in corporate revenues and earnings, which in turn drives returns from equities and other assets.

The SDGs aim to create a viable model for the future in which all economic growth is achieved without compromising our environment or placing unfair burdens on societies. Embracing the relationship with society, the environment and government creates a new strategic lens through which to view and judge business and investment success.

In the last 10 years, responsible and impact investment has evolved from being a primarily exclusionary approach to one focused on identifying companies that can effectively manage ESG risks and opportunities, while achieving impact. The challenges put forward by the SDGs reflect that there are very specific regulatory, ethical and operational risks which can be financially material across industries, companies, regions and countries. They provide a common way of referencing the move towards a more sustainable world, and can thus strengthen investors’ ESG risk frameworks as well as focus in on impact investment actively contributing to social and environmental solutions and transformations.

In many cases, investors and philanthropists are implicitly taking these factors into account already. The SDGs offer a common language with which to shape and articulate such investments and philanthropic strategies, as well as a sense within which to think about selecting charities.

RESOURCES:

https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/pdf/philanthropy-impact-magazine-issue-26-pt1_final.pdf

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/

https://access-socialinvestment.org.uk/us/total-impact-approach

https://www.schroders.com/en/insights/economics/what-are-the-uns-sustainable-development-goals-a-quick-guide

https://www.maanch.com

https://updates.maanch.com/2020/11/how-to-reallocate-capital-for-impact

https://thegiin.org

https://toniic.com

https://www.impactinvest.org.uk

https://updates.maanch.com/2021/02/esg-going-beyond-risk-mitigation

SUGGESTION 1:

“Investing and giving for good: homelessness: it’s impact on the economy”

by Shakeel Adli, Autumn 2023

SUGGESTION 2:

“The celebrity philanthropist – impact investing for social and environmental change”

by Simon Voisin, Winter 2022

SUGGESTION 3:

“What is social impact investment, why is it growing and is it really having an impact?”

by James Westhead, Winter 2022

SUGGESTION 4:

“What does impact investing really mean?”

by Alice Millest, PI Magazine, Summer 2019

ESG

SUGGESTION:

“The Investor Revolution”

by Robert G. Eccles and Svetlana Klimenko, Summer 2019

WOMEN WITH WEALTH

SUGGESTION 1:

“Letter to the editor”

by Ise Bosch PI Magazine, Autumn 2018

SUGGESTION 2:

“An invisible opportunity: Engaging women of wealth around philanthropy”

by Leesa Muirhead PI Magazine, Autumn 2018

SUGGESTION 3:

“A brave new world of philanthropy”

by Isabelle Clough PI Magazine, Autumn 2020

SUGGESTION 4:

“Editorial: Millenials and women of wealth – an opportunity or pitfall for advisors?”

by Cecilia Hersler, PI Magazine, Autumn 2018

MILLENNIALS

SUGGESTION 1:

“Awakening the millennial philanthropist – a guide for professional advisors”

by Lauren Janus PI Magazine, Spring 2018

SUGGESTION 2:

“Millennials are seeking professional advisers who understand their values”

by Charles Peacock and Charlotte Filsell PI Magazine, Autumn 2018

SUGGESTION 3:

“Next Generation Philanthropy – What matters to millennial mega-donors”

by Michelle Wright PI Magazine, Summer 2020

SUGGESTION 4:

“Why next gen philanthropists are being set up for failure”

by Jake Hayman, PI Magazine, Autumn 2018

The Role of Professional Advisors

An evaluation process for judging/selecting professional advisors and how to deal with those relationships.

To enjoy a successful and satisfying philanthropy, social investment or impact investing experience, a professional advisor is useful to help guide you. A professional advisor may be a private client advisor, and/or work in the wealth management, private banking, independent financial advice, tax or legal sectors.

A professional advisor can be particularly helpful when first getting started, when time is a constraint, when there is increasing complexity or when you are giving and investing significant amounts. A professional advisor can best support your giving practice – reducing risk when deploying money, increasing your knowledge and ultimately leading to a successful philanthropic engagement.

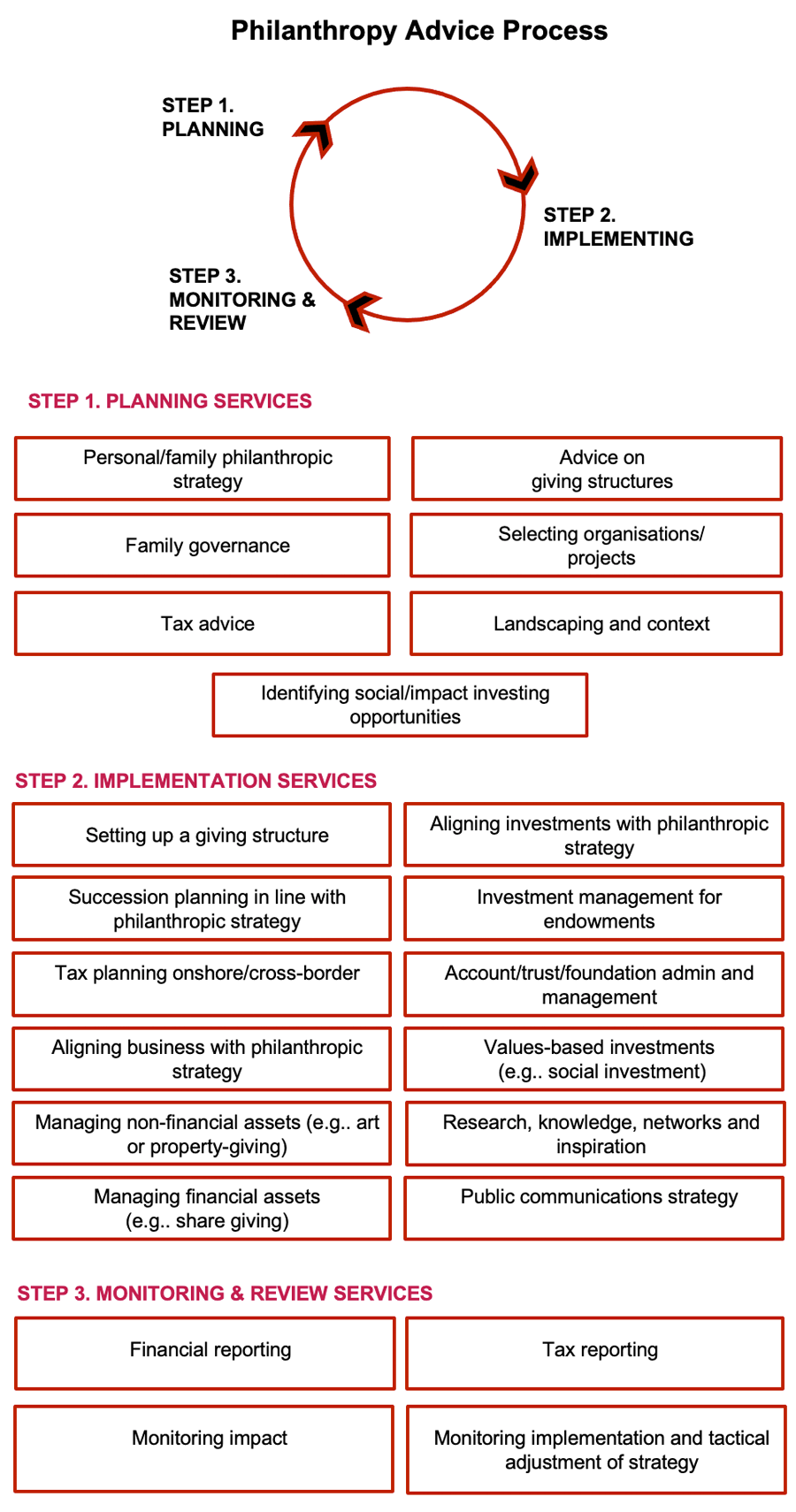

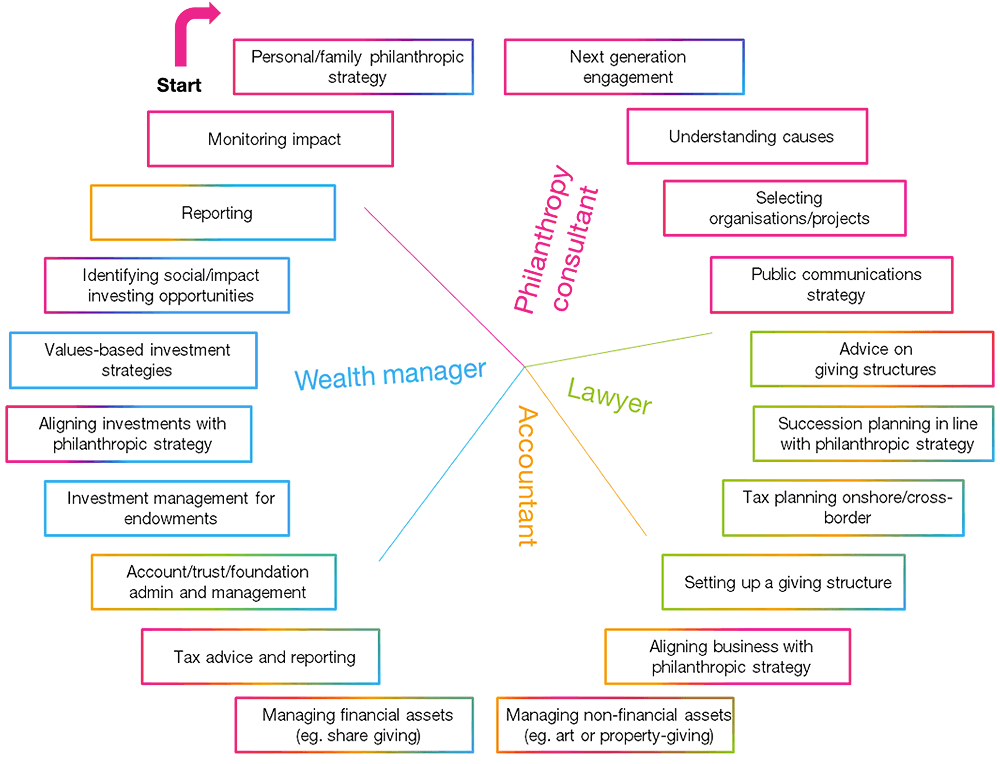

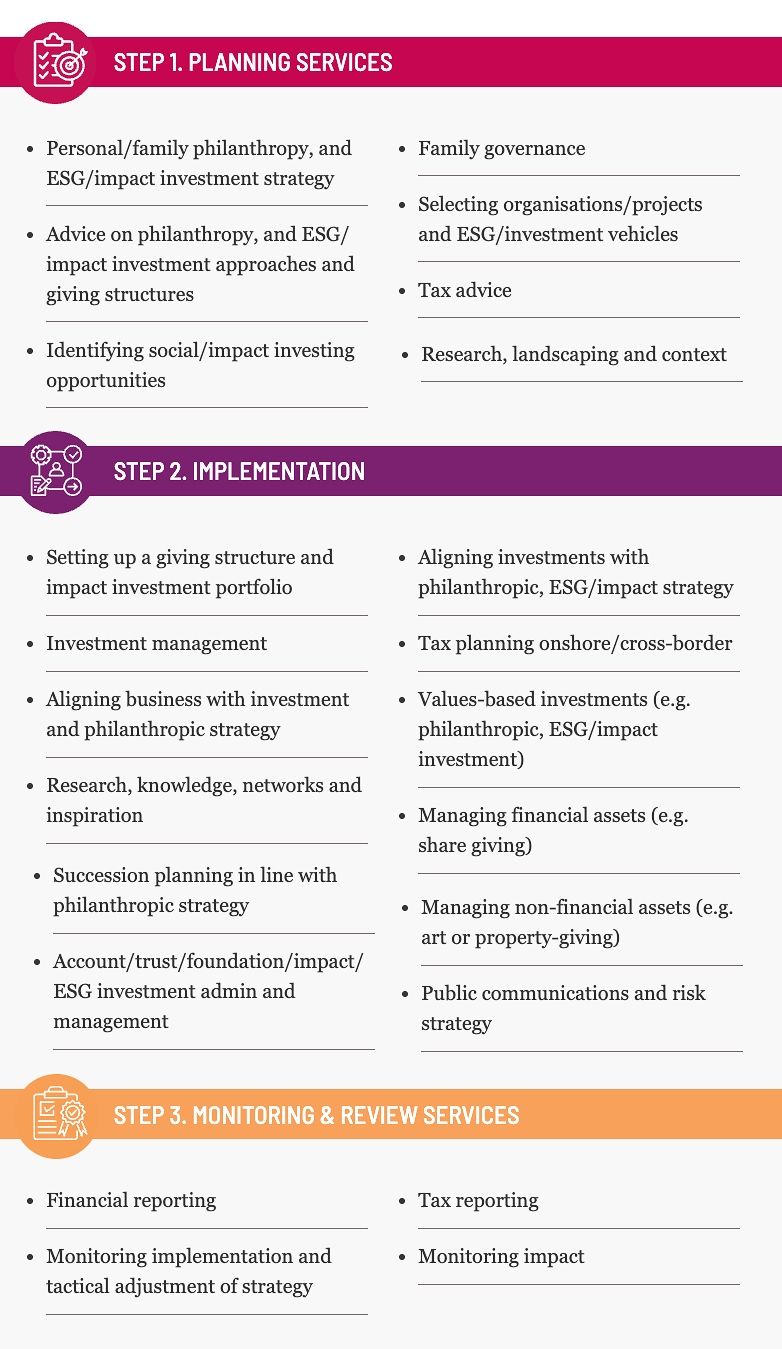

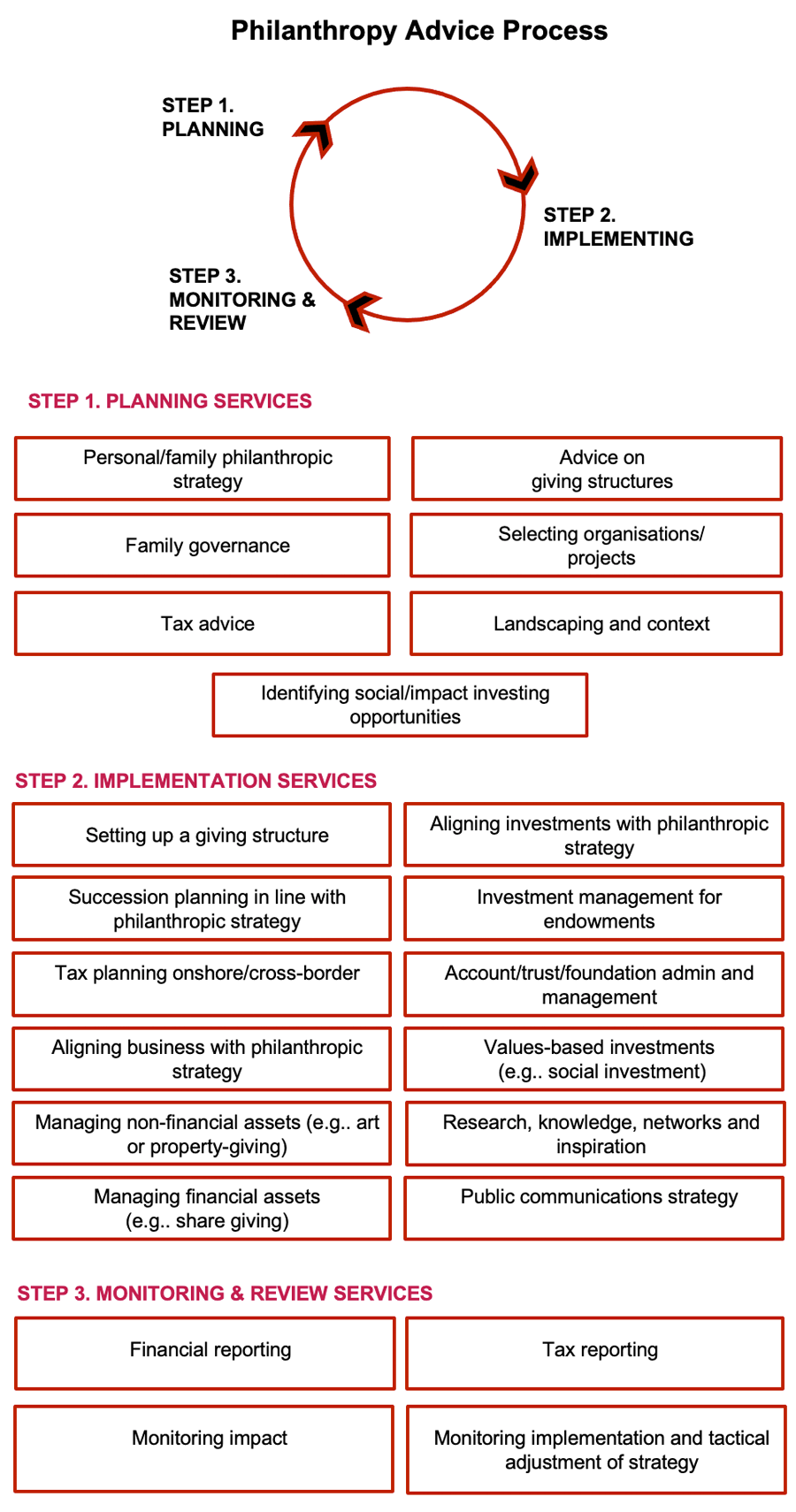

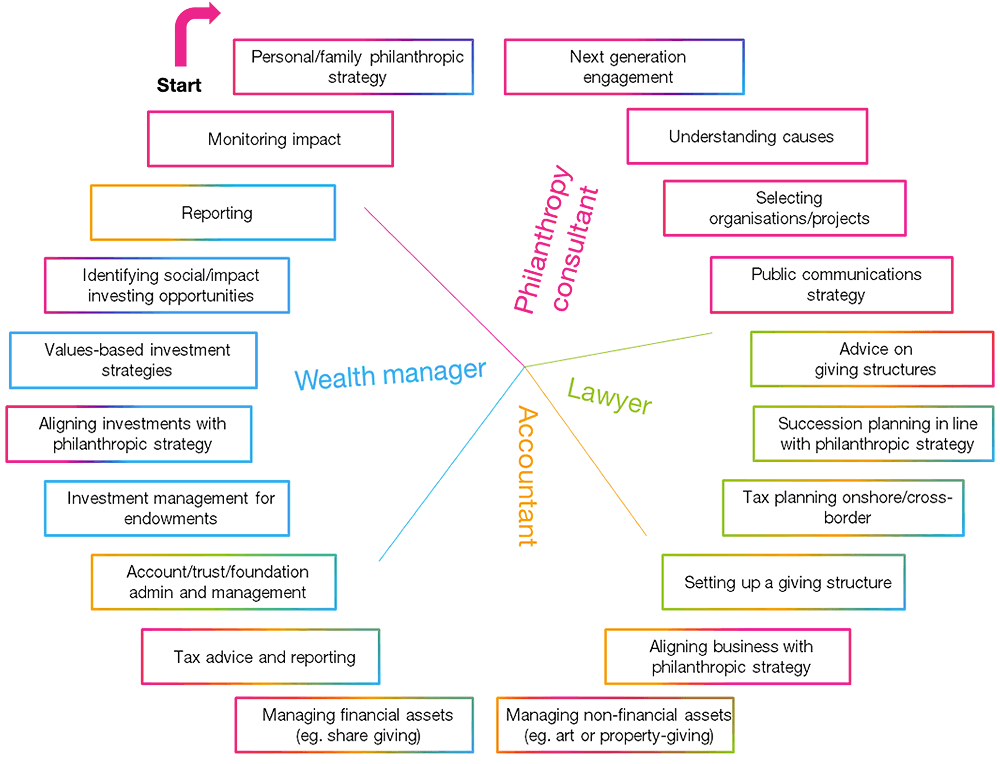

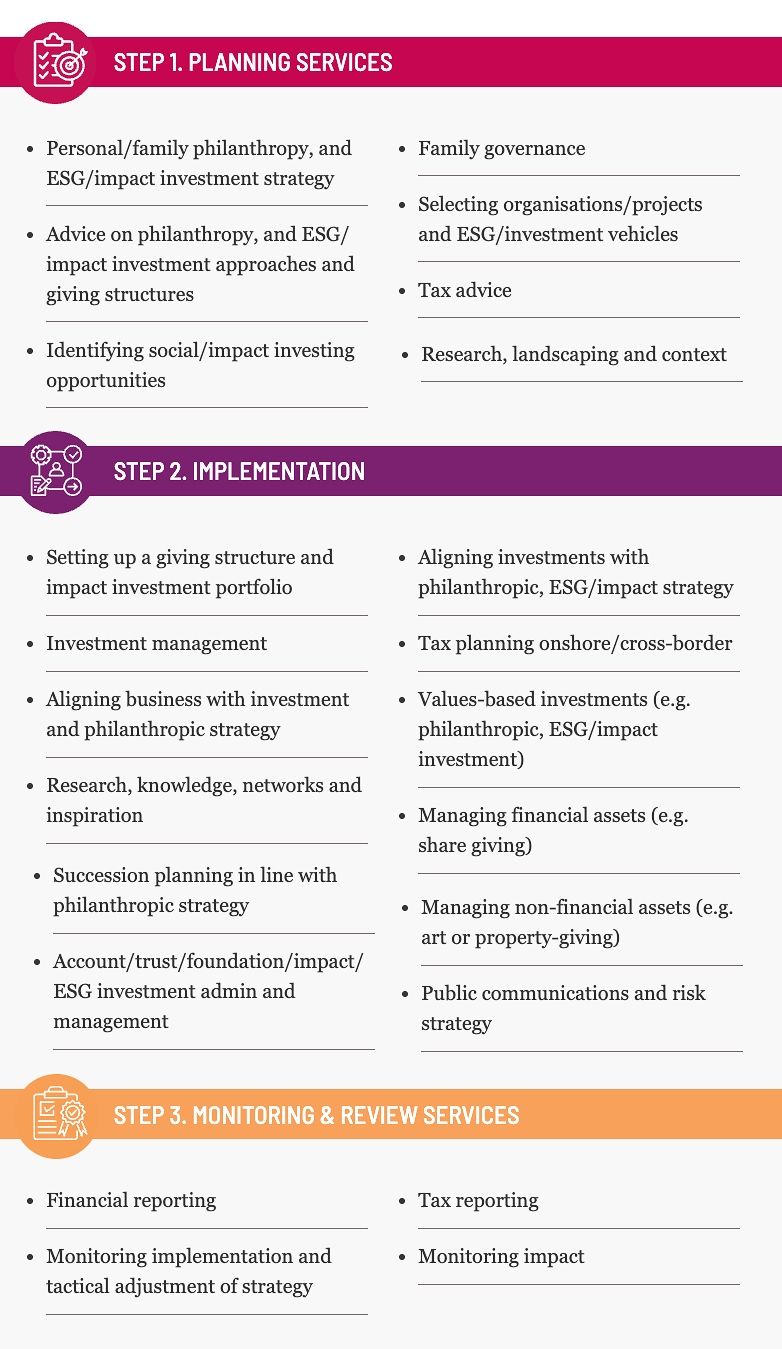

Keep in mind that, over their donor journey, a philanthropist may need 23 distinct services from multiple professional advisors. See below for examples.

Philanthropy advice has the same steps as other professional advice

Multiple advisors Act In Different Parts of the Advice Chain

How best to select an advisor? You might engage with several advisors along the way, for example, a lawyer to help set up a structure or a wealth manager to invest in charitable funds. They can also help guide you through social impact investing and its contribution to your philanthropic goals.

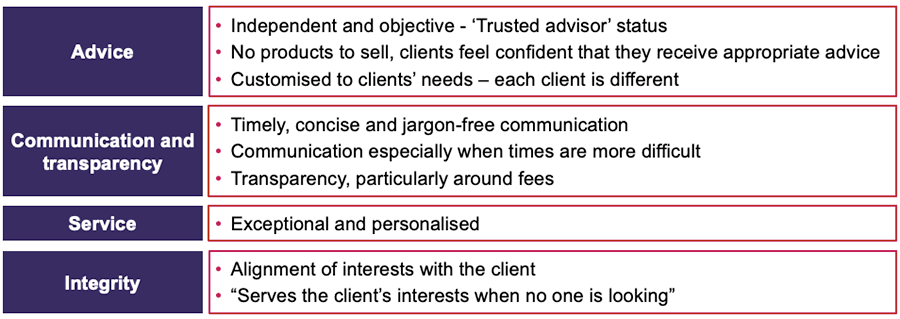

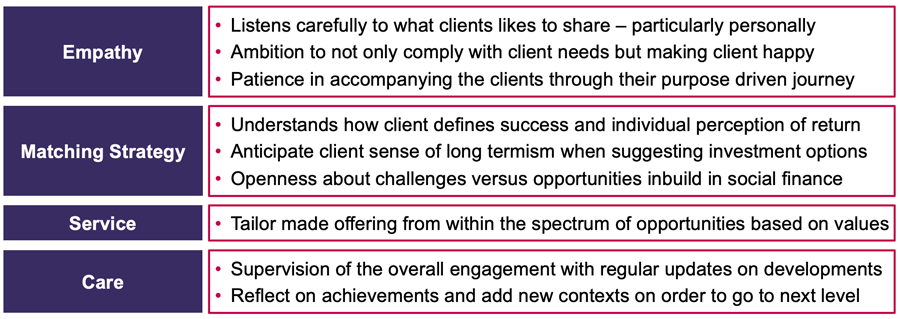

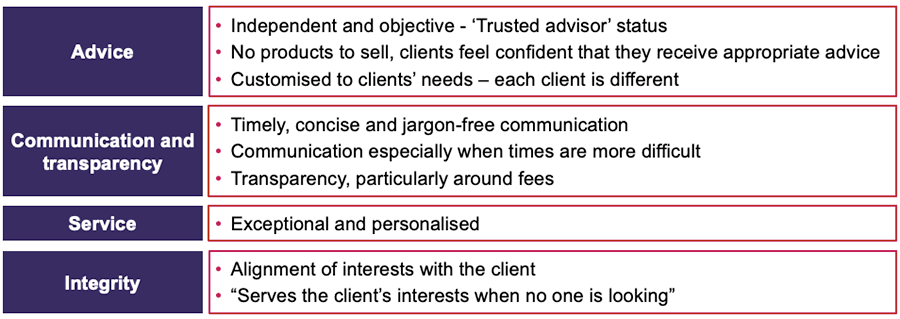

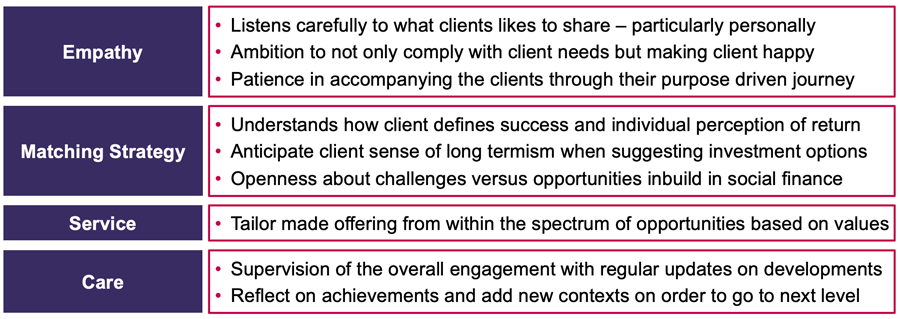

The following is some useful criteria for you to use in selecting a good advisor.

What Makes A Good advisor?

What Makes A Trusted advisor?

An evaluation process on how to judge/select philanthropic advisors and how to deal with those relationships.

What services can a philanthropic advisor provide?

(see A guide to working with Philanthropic Advisors, Fidelity Charitable)

- They can help design a strategy or plan for giving.

Philanthropic advisors can help donors clarify their values, mission and goals. A philanthropic advisor will listen to donors’ charitable interests and priorities and work with them to document and define an approach that meets their needs. This support gives shape and brings clarity to a donor’s ideas and helps translate them to action.

- They can support and facilitate discussions among families.

Giving together as a family can be a rewarding experience, but it’s not always easy. Philanthropic advisors give families the tools to examine individual family member’s interests and desires to participate in family philanthropy and then use that information to define each member’s role in the family’s philanthropy and to support them in deciding where and how they will focus their resources as a group and/or as individuals.

- They can identify giving opportunities and carry out plans.

Some donors know what causes are important to them but still need assistance finding the right non-profits and giving opportunities. Philanthropic advisors use their expertise as well as their professional relationships to match a donor’s charitable vision with suitable organisations or projects — and they can help structure the funding agreements, too.

- They can evaluate the impact of donor grants.

Results-oriented donors can rely on philanthropic advisors to help them understand how, and if, their giving is leading to the outcomes they hope to achieve.

- They can identify other aligned funders or learning partners.

Philanthropic advisors can help donors who wish to make a bigger impact in a specific area to identify like-minded individuals with whom to meet and collaborate.

- They can coordinate with investment advisors and financial planning experts.

Philanthropic advisors are less focused on tax and financial planning and more focused on matters related to the distribution of charitable assets. However, they may work with a donor’s financial advisor, tax attorney, estate planner and other experts who play important roles in helping an individual determine which assets to give to charity and when, which giving vehicles are most appropriate, and how best to integrate charitable giving goals into broader financial plans.

WHEN DOES A DONOR NEED PHILANTHROPIC ADVICE?

Individuals and families decide to work with a philanthropic advisor for different reasons and at different stages of their lives. Here are some common situations where donors may look to an advisor for clarity and support.

- When philanthropy requires more time and focus than a donor can give.

People who’ve dipped a toe in financial planning know how time-consuming it can be — in fact, it’s one reason why many households hire financial advisors. Philanthropic planning can be equally complex. A philanthropic advisor can assist busy individuals and families with the research and evaluation of non-profits, including deciding where to give, how much to give and over what length of time. Many dedicated givers also feel overwhelmed by the number and frequency of requests they receive from non-profits. Advisors can help by managing relationships with non-profits, especially for donors who prefer to remain anonymous. They also can step in to help clients focus on the causes and issues that matter most to donors, and support them in developing a tailored, proactive plan for their giving.

- When a change in finances leaves a donor with more to give.

A philanthropic advisor can help individuals who have experienced a financial windfall and have more to give than in the past by working to clarify their charitable priorities and motivations. Having a well-defined plan in place allows donors to feel more confident in their decision-making around giving, especially when giving at significant levels.

- When a donor wants in-depth information about a cause.

Philanthropic advisors use their expertise to research topics or issues a donor may be considering supporting. Advisors may look for key opportunities for philanthropic funding and identify high-impact organisations that are working in a particular sector or area.

- When a donor wants to understand charitable impact.

A philanthropic advisor can help a donor track the impact of her giving by monitoring and evaluating the grants she has made to non-profits. Following up with non-profit staff and analysing reports provided by organisations help an advisor determine if a donor’s charitable aims are being met. This tracking also can inform discussions about potential adjustments to a giving strategy.

- When important life events impact a family.

When a family experiences a liquidity event or significant life event, such as a marriage, birth or death, the responsibilities and activities of those involved in the family’s giving may also experience transition. Sometimes this change is best navigated in multigenerational families by an independent party, such as a philanthropic advisor. An advisor can support the conversations and provide guidance around the family’s giving choices and how those may be continued or altered. An advisor can also help a family that’s just getting started in charitable giving by making sure members are answering important questions about the roles, level of involvement and extent of collaboration expected from everyone. Cooperation at the beginning of philanthropic planning can pave the way for greater agreement and more impactful giving decisions as the months and years pass.

- When a donor wants help to design and manage significant legacy gifts.

Philanthropic advisors can provide accompaniment to ensure that legacy gifts have long-term benefits to the organisations they choose to support.

WHAT SHOULD A DONOR CONSIDER BEFORE WORKING WITH A PHILANTHROPIC ADVISOR?

In the right circumstances, a philanthropic advisor’s expertise can elevate a donor’s charitable giving. Here are a few important elements that donors should consider as they think about hiring a philanthropic advisor to make sure they make the most of the relationship.

- Level of openness and receptivity to help

As with any consultant who assists individuals with their goals, a philanthropic advisor can be a powerful partner — but only if donors are receptive to advice and make themselves available to their advisor. Willing discussion is critical in working together to plan and achieve charitable aims.

- Role for other family members and advisors

In many situations, the work will be most effective if family members and additional professional advisors engaged by a donor, such as financial planners, are supportive of the effort and available to participate in the process as appropriate.

- Priority areas and needs

There are several approaches to working with a philanthropic advisor and several ways an advisor can help. To make the most of the investment of time and resources with an advisor, donors should be clear on the nature of their needs and their priorities and structure the engagement accordingly.

- Short term

Many individuals engage a philanthropic advisor for a single, limited project, such as to define a giving plan or to prepare for a family transition that will alter giving roles. An advisor serves as a short-term consultant in these scenarios to assist with a temporary need.

- Long term

Some donors require a philanthropic advisor’s assistance for an extended amount of time, such as to support the management and execution of a long-term giving plan that requires consistent assessment and attention. In this case, the advisor may serve as an alternative to hiring staff to support one’s philanthropy.

- Occasional

Dedicated givers who have ongoing but undefined needs may engage advisors to provide occasional counsel. These advisors can serve as a sounding board when working through questions related to specific gifts, family dynamics or other challenges that arise.

HOW CAN DONORS FIND AND EVALUATE A PHILANTHROPIC ADVISOR?

When a donor has established her reasons to engage expert help in charitable giving, the next step is to locate a philanthropic advisor who speaks to both her needs and her operating style. These tips will guide donors in that process.

Research the right fit and qualifications

Reputation

Donors are wise to investigate the background and experience of the firm or individual they are considering for philanthropic help, just as they would any other type of consultant. It’s crucial to confirm that advisors are trustworthy and have a successful track record. Speaking with references can be particularly useful when evaluating the quality and experience of a philanthropic advisor.

Chemistry

A philanthropic advisor should have a style, approach and philanthropic philosophy that aligns with the donors’, so spending some time talking with an advisor and getting a feel for how he or she works before formalising an engagement just makes sense. References also are helpful here. Donors should be comfortable sharing any personal challenges or goals with their advisor and feel confident that an advisor has the expertise to do the work asked of them; they should also get a sense that the advisor will listen to all parties involved in giving. An advisor must be able to work well with all the people and entities that have a hand in a donor’s charitable giving.

Experience

It goes without saying that an advisor should have demonstrated experience working in philanthropy — and specifically in the areas where a donor needs assistance, whether that means working with families or structuring complex international gifts. Experience as a grant-maker and access to networks in the communities where the donor is trying to make change are also very valuable assets. Philanthropic advising encompasses more than simply disbursing gifts; it includes providing thoughtful strategic input, creative problem-solving, and knowledge of and appreciation for the dynamics between grant-maker and grant recipient.

HOW DO DONORS STRUCTURE AN ENGAGEMENT AND ASSESS FEES?

The contract structure and associated fees for an engagement with a philanthropic advisor will depend primarily on the specific nature of the work requested. For example, using a philanthropic advisor to organise a family retreat for charitable planning will have a different scope and fee structure from defining, building and providing support for a multi-year giving plan. However, any engagement with a philanthropic advisor should have a well-defined plan, including deliverables and a timeline, to achieve the donor’s goals.

A few common pricing models include:

Project-based fees

The advisors’ fees are fixed and tied to a defined scope of work. This model may be most helpful in cases where the advisor is being hired to conduct specific research or facilitate a meeting or set of meetings.

Retainer model

The advisor is available to help a donor on an ongoing basis. This model is often useful for donors who need support across many different areas of giving, and over a long period of time, but don’t need a full-time staff member.

Hourly fees

This model is most helpful if a donor wants the greatest flexibility in working with an advisor, allowing the donor to engage the advisor on an ad hoc and as-needed basis to support a donor’s learning process, support a strategic planning process that may evolve over time, serve as a sounding board, answer specific questions, or assist in other ways.

Donors may hire and pay philanthropic advisors personally or, in some cases, a charitable entity (e.g. a private foundation or donor-advised fund sponsor) may hire and pay the advisor.

Choosing a Professsional Advisor: Due diligence

- What does being a trusted advisor mean?

- Be clear about your needs, what type of advisor(s) is needed (wealth management, tax planning, philanthropy) to meet your needs?

- Outline the criteria you should set for the advisor of choice

- How do you assess your advisor? See competency framework below for potential areas to discuss including planning, implementing, monitoring/review (including measuring impact) related to both advisors supporting a client on their philanthropic and impact investing journey

Note items:

- 1 - 3 cover both impact investing and supporting clients on their philanthropic journey

- 4 - 7 cover supporting a client on their philanthropic journey

- 8 - 10 cover supporting clients on their impact investing journey

- 11 - 12 cover generic issues applying to philanthropic giving and impact/ESG investment

| Competencies |

Leaning Outcomes

|

- What is impact investing including investments and assets (financial and non-financial) and how does it differ from ESG investing

|

A general understanding of approaches to investment and asset management (financial and non-financial) and how these relate to philanthropic strategies (both financial and non-financial returns)

|

A general understanding of investment management and how to signpost clients as needed, a good understanding of how investment and asset management needs inform a client’s agreed philanthropy and impact investing planning assumptions

|

- Approach to creating an investment portfolio and approach to due diligence

|

A general understanding the key aims of impact investing

|

A general understanding of achieving environmental/societal (SDGs) return along with a financial return and of the context of impact investing and where it fits in and is differentiated form the other approaches on th spectrum of capital

|

- Overview of social investment

|

An up-to-date understanding of social investment approaches and the range of social investment vehicles used

|

A comprehensive understanding of social investment approaches, intermediaries and their role and how to sign post a client to them, understanding the client’s priorities for social investment, understanding the client’s objectives and time horizons

|

- Personal philanthropic and impact investing strategy withing and understanding of the spectrum of capital

|

A good understanding of client needs and how to reflect their philanthropic and impact investment priorities in any wealth management strategy; being able to develop strategies for philanthropy and impact investing that reflect the client’s values, motivations and priorities

|

A good ability to identify and articulate the individual client’s values, motivations, objectives, needs, and constraints, including client attitudes, biases, drivers, preferred social or environmental causes and willingness to investigate other social issues – potentially within the D+SDGs context

|

- Family philanthropic and impact investment strategy (if applicable)

|

A good understanding of family philanthropic and impact investment strategies; being able to develop strategies for philanthropy and impact investment that reflect the family’s priorities

|

A good ability to identify and articulate the family client’s objectives, needs, values and constraints, including attitudes, biases, drivers, succession and legacy planning; preferred social or environmental causes and willingness to investigate other social issues

|

- Tax relevant tax understanding

|

A good understanding of the implications and advantages for tax efficiency relating to philanthropic and impact investing giving

|

A good ability to determine the client’s understanding of various tax approaches and signposting clients to appropriate support

|

- Philanthropic Giving structures

|

An up-to-date understanding of what giving structures are available for philanthropy

|

A good understanding of different structures and the pros and cons of each one i.e. a Foundation or a DAF or Gift Aiding in order to develop and manage the client’s philanthropy strategies

|

- Philanthropy landscape and context

|

A good understanding and up to date broad knowledge of how charities, non-profits and social enterprises operate and the current philanthropic trends

|

A good understanding of the philanthropic and charitable sector landscape, emerging trends that are impacting the sector and how these might influence client decisions, how charities operate and their governance principles, how planned gifts (deferred and current) and major gifts are cultivated, solicited and stewarded by charities, understanding how to work with charities to communicate and address the interests of clients

|

- Selecting organisations/ projects for philanthropic giving

|

A good understanding of grant-making policies and processes that are most commonly used, monitoring and evaluation approaches and how to commission external support in this area

|

An up-to-date understanding of charity law and how it applies to donations and grant-making (including for non-charities), designing a grant-making programme in line with a client’s philanthropy strategy, assessing charities and assess grant applications, monitoring and evaluating progress during and after the grant period, identifying appropriate reporting priorities and dealing robustly with ‘problem’ grants

|

- Impact measurement

|

The purpose of and issues/challenges related to measuring and reporting impact/outcomes and outputs for philanthropic giving and impact investing

|

An understanding of the purpose and value of impact measurement and of impact management and measurement including principles, frameworks, standards and tools

|

- Risk and communications internal/external and the importance of due diligence and suitability discussions

|

An understanding of the different risk profiles of different philanthropy approaches and gift types, funds, intermediaries, and how to appropriately assess for risk within a philanthropic / civil society landscape, and effectively using strong interpersonal communication skills with clients, colleagues and other professionals; and of risks related to impact investing and the importance of suitability discussions as part of customer centricity

|

A good ability to determine the client’s risk management objectives, risk exposure and tolerance for risk exposure (including willingness to take steps to manage financial risks)

|

|

Building and maintaining effective relationships with clients in order to discern client intent, values, motivation, interests, passions and proactively developing connections with a wide range of people across different sectors to support and inform philanthropy strategies

|

- Inspiration and learning

|

Up-to-date skills and knowledge, understanding of the key issues surrounding philanthropy and impact investment

|

An understanding of the need for ongoing professional development and reflective learning, including training in advisory expertise

|

- Seek referrals from friends/peer group, family, trusted advisors

- Research firms and individual advisors and their teams (USP/what sets the firm apart from other firms, ownership structure, assess built in bias/conflicts related to the firms values/structure/culture/impact/approach to sustainability and impact investing, any regulatory issues/government investigations involving the firm or individual advisors, plans present and future, regulatory context, websites, client testimonials, credentials and qualifications, experience/track record, range of services offered/educational support/resources, resources, approach to technology)

- Arrange an interview to discuss your needs and to assess the fit of services to need, their and their firms and advisors values and approach to sustainable investment, their ability to support you across the spectrum of capita, their approach to goal setting/suitability/SDGs as part of the decision making process including process of identifying/evaluating/selecting investment opportunities, communication, their level of professionalism. Ask about their approach to client relationships, investment philosophy/impact investment and measurement expertise and experience, and how they address complex financial challenges, and what your intuition is telling you about whether there is positive chemistry trusting your instincts, and all potential fees (including compensation they receive from selling investment products and how does the firm address conflict of interest re advising a cleint and selling a product.

- Check references/samples of reports/due diligence memos (redacted)

- Make final choice – will they be your first call

- Ensure the onboarding process is focused on relationship development

Keep in mind that a philanthropist will need 23 distinct services on their philanthropic (and impact investing) journey.

THE 23 SERVICES

Philanthropy, ESG and impact investment advice has the same steps as other professional advice

The listings are related to the 23 services that Philanthropy Impact has already identified as being essential for effectively supporting you across the spectrum of capital.

For further information on the 23 Services, please visit 23impact.org

The Seven Stages of Giving

Our seven-stage framework will help you on your philanthropic and social investment journey. Click on each stage of the framework to see advice and case studies from other philanthropists who have addressed the issues you might now face. This is not a linear journey and any stage can be revisited at any time.

STAGE 1: VALUES COMPREHENSION

- Understanding your motivation and identifying your guiding values and ambitions, and how this fits into the bigger picture of your personal situation.

- Values develop out of a dynamic process and are the basis for responsible behaviour that leads to societal transformation. The typology of values is vast and includes personal values, values related to work life and values embedded in the culture.

- Values can shift personally and often they reflect cultural change processes and are the prerequisite for a changing world. So, it is about the identification and formulation of personal values in the context of a changing environment. Common values are integrity, respect and responsibility, but there are many more. They reflect our sense of right and wrong and our internal compass. Your values are the things that you believe are important in the way you live and work.

Here are a few useful prompts to help you define your values:

- Once aware and connected to one’s own values, a vision usually emerges of how we want to be and also a sense of what we really want.

- “Visioning means imagining, at first generally and then with increasing specificity, what you really want. That is, what you really want, not what someone has taught you to want, and not what you have learned to be willing to settle for. Visioning means taking off the constraints of ‘feasibility”, of disbelief and past disappointments, and letting your mind dwell upon its most noble, uplifting, treasured dreams.” (Donella Meadows)

- It is in our best interests to be clear about our vision. Vision is not simply a memory, but a living and specific awareness of intention. It is a conscious integration of mind and heart, and the best starting point for a complex ambition requires learning and collaboration. It allows you to utilise all of your talents and capabilities, both explicit and implicit, and opens your awareness to emergent and unexpected resources and support.

Motivation and Context

Closely aligned with vision and values, it is important to also understand one’s motivations. Most of us have reflected on how to express what we care about. But can we explain clearly what we want to achieve with our giving? Such knowledge can help define a philanthropic plan of action and maximise its impact.

“What is your wealth for?” and “Why do you like to engage?” are central questions. Being or becoming aware of opportunities to make a difference aligned with one’s own vision and personal set of values may well be overwhelming. It is important to be clear about your own motivation to engage as this helps to take clear steps to make the giving successful, impactful and self-rewarding.

It is important to identify values, personal motivations and ambitions as well as to understand what personal fulfilment would look like. What would you like to achieve? What are your ambitions?

What does success mean and what would it look like? These are likely to change over time as one learns more throughout the journey and adapts the strategy accordingly.

At the outset, it important to understand your motivation in context. Typically, this could have developed out of a family tradition, a desire to encourage your children to reflect on wealth, a wish to engage with communities, the urgency to make a difference or leave a legacy, personal fulfilment or more strategically just doing ‘good’ and acting responsibly.

Other questions to consider are “What are you passionate about?”, “what issues or causes do you wish to address?” and “what do you want to be remembered for?”

Here are some key reasons why people start their philanthropic journey:

- Responsibility: having created wealth they feel a responsibility to give back to the individuals and society that helped them on their way. They wish to align their values with their money.

- Family values: they come from a family that gives, or they want to demonstrate to their children the importance of empathising with those who are less fortunate.

- Peer group: they are part of a community (often religious) that gives and they continue in that tradition.

- Life changing event: whether selling a company or coming to terms with a tragic event, life changing events often change the priorities of individuals. They may have more time on their hands and want a new challenge. Or they may have very personal reasons for focusing on a particular cause.

- Legacy: for some wealthy donors the desire to leave traces of a well-led life is a powerful motivator. Others leave gifts to charity for estate planning purposes or because they don’t have children to whom they can pass their wealth.

- Restructuring for wealth and estate planning: others leave gifts to charities for estate planning or because they don’t have children to whom they can pass their wealth on to.

Suggestion 1:

“How To Give It: meet the wealth therapist”

Emma Turner is on a mission to awaken the philanthropist within, Chloe Fox February 5th 2020

Suggestion 2:

“Our Responsibility to act”

by Leslie Johnston PI Magazine, Summer 2020

Suggestion 3:

“Dealing with complexities collectively”

by Urszula Swierczynska PI Magazine, Summer 2020

Suggestion 4:

“An invisible opportunity: Engaging women of wealth around philanthropy”

by Leesa Muirhead PI Magazine, Autumn 2018

Suggestion 5:

“Giving Tomorrow”

by Legacy Foresight, 2019

Knowledge Base and Learning Curve

Advice from peers or professional advisors can help on this road to impactful philanthropy, but you need the skills to find the information needed. You need to ask the relevant questions and develop the ability to tell the difference between good and bad charitable projects.

Everybody brings a set of skills, as well as general or specific knowledge and experiences, to the discussion. But embarking on a philanthropic journey means continuous learning and understanding of the challenges.

At some stage a field visit may even be useful to help better understand current giving practices and also how these could be improved.

Are you ready to embark on a philanthropic journey? Are you feeling like you want to live your life on purpose, but you don’t quite know how to get started?

Dipping your toe in the philanthropic waters is like starting a journey without knowing where you’re going. So begin by exploring what issues and problems matter to you. Learning from experts about the issues that you have identified is a smart starting point as you experiment with some modest grant-making. You’ll quickly discover that the needs in your community and in the world are vast and your time and resources finite. More critical thinking, exploration and discernment become a must, and a more concrete learning agenda and clear plan of action become essential.

According to Peter Karoff, founder of The Philanthropic Initiative, there are six stages to the philanthropic learning curve.

- Become a donor. You may be thinking about your legacy, your position in the community or your desire to go from success to significance. You respond to many, many requests and you likely give in small amounts to large numbers of organisations. In this novice approach you spread your dollars across a wide variety of causes and organisations.

- Get organised. You may feel like you don’t have any control over the process. You have a pile of requests on your desk and you are being reactive instead of proactive, so you want to take a step back and begin to determine your priorities and approach.

- Become a learner. You realise that philanthropy is hard and you want to engage in learning about the issues that are important to you. You want to know which are the most innovative and impactful non-profits on the cutting-edge of the work, and by extension, the organisational leaders who are devoting their time, energy and resources to addressing important issues. You begin to distinguish philanthropy from charity.

- Results oriented. You want to begin to make a difference and determine if and how your investments can make an impact. You become more discerning as you become more educated about issues, approaches to addressing those issues, and the organisations and people who are providing, championing and piloting solutions to problems. You search for the leading people and organisations which are making a measurable difference.

- Leveraging your philanthropy. You gain the clarity to either develop or fund programmes that meet specific objectives. You consider collaborating with other funders and learn from others who have invested in a variety of solutions before you.

- Alignment. The alignment of community impact and personal fulfilment happens when you have clarity of your vision, passion, and interests, and these dimensions come together to achieve your goals. This coherence is when philanthropy is exciting and satisfying. Ultimately, philanthropy works when a critical social need has been identified and the gift has fulfilled that need. That is alignment. That is at the heart of philanthropy.

Karoff goes on to list the following question as the primary test of philanthropy:

Was our purpose noble, were we true to it, and did we in all instances, deeply listen to the community of interest we presume to serve?

STAGE 2: EMERGENCE OF A VISION

A vision statement should express one of two things – either a vision of what you expect to achieve or aspire to be; or a vision of how society will be different if your approach achieves your mission, describing desired outcomes and impact. It is our ideal future, our aspiration.

A well-defined vision statement gives meaning to the work of the philanthropist and aligns philanthropic giving under a common intent. It answers the big questions: “Why are we doing what we’re doing? What are we really trying to achieve?” The vision statement should outline one’s expectations, aspirations and performance, and should inspire feelings of enthusiasm, hope and pride.

Key questions to consider when defining your vision:

- Describe the community/cause you would like to address

- What is the nature of this community’s problem that you would deal with?

- How would things be better and/or different for them if this problem were solved?

- What is your ultimate hope for this cause?

Mission & vision

- Setting clear objectives can be taken one step further by writing a vision and mission statement.

- A donor’s vision is an inspirational, long-term view of the kind of world they would like to see, while the mission defines how they are going to try to achieve that vision. Some donors like to set out in writing their vision and mission, either to guide their own internal strategy, or for external purposes — for example, for potential grantees or other funders, if you have a charitable trust.

- A mission statement is not a replacement for setting objectives or defining funding criteria, which go into much more detail about your wishes and plans. Instead, the vision and mission statements should be short (one or two sentences), inspiring, durable (designed to last five or more years) and distinctive.

Why have a vision and mission statement?

For many donors thinking about their giving plans, setting clear objectives of what they want to achieve is one of the first stages. The vision and mission statement can give a clear sense of direction to trustees and a framework within which to set and review objectives. It can provide a sense of clarity to external audiences on what the foundation is trying to achieve. And the process of setting out in words the world you want to see, can really help you to clarify your values and beliefs, and express the most important aspects of what you are trying to achieve with your giving.

How to write a vision and mission statement

It can take time and effort to devise a well-written vision and mission statement, but it is worth the effort. Depending on how you are giving or with whom, the process can be helped by involving others —board members, family members, staff and external advisors. When writing your vision statement, try to articulate the world you would like to see, incorporating your values and beliefs. Your mission statement needs to set out why you are giving and what you will do to work towards this broad vision.

Deciding how to support a charity

Once you have set your vision and mission, think about how you would like to execute. There are many ways that you can make valuable contributions to a not-for-profit.

Financial support will certainly be top of their priority list, be it immediate support or longer-term giving, like a charitable bequest. You can also provide support by raising the charity's profile and opening your network to them, once you have established a relationship. Other types of support, include offering your skills or goods and services. Or even all of these! This provides a great opportunity to really integrate purpose into a business and a great tool for engagement with employees and other stakeholders.

Maybe you know of an organisation which is doing great work but struggling in some capacity, and you can see ways in which your skills could help them address these difficulties. Or perhaps you have spare time and would enjoy the challenge of applying your skills in a different context, while making a real difference to a cause you care about.

Before you begin exploring opportunities to give your time, first assess what commitment you can make and over what period. If your commitments are unpredictable, it is vital to be clear about this and plan your engagement accordingly. Trustee or board positions should be a longer-term commitment, as the charity will need to invest resources in your induction. However, the charity may benefit from shorter-term support such as business planning or strategy coaching.

Keep the following in mind when selecting a charity:

- The investment-return continuum

- Key steps in preparation: assessing one’s values/motivations/desired impact, researching/selecting, setting goals, developing a strategy and budgets

- The research stage includes seeking advice, meeting other donors, and specialist advisors, as well as deciding how much you want to do and what you want to outsource to advisors

- Decide whether and/or how to involve family and next gen/millennials

- Explore and decide how to structure giving e.g. tax issues, vehicle (daf, trust etc)

- Learn how to choose and select a charity/social enterprise, and apply within your strategic context

Additionally take a due diligence risk management approach:

- Collect basic information on the targeted charities/social enterprises

- Desk research, identify other funders, review annual report and accounts, understand the vision/mission/strategic priorities and key individuals

- Assess governance, risk management/how they are mitigating risks, board and CEO evaluation processes

- Ask for a business case from the charity, re the charity as a whole, and as part of the specific area of interest e.g. service need/problem, right strategy and solution, USP, people to make it work, the ask and returns (financial and societal/environmental)

- Review evaluations of the charity/social enterprise and its impact

- Assess financials as you would a business e.g. cash flow, deficit/surplus, reserves, income sources included restricted/unrestricted

Support at a strategic level

If you decide to donate your skills by supporting the senior management or strategy development of the organisation, ensure that you jointly set clear objectives and establish when you want to achieve them. This helps set expectations of all parties and provides opportunities to celebrate achievements.

Finally, it may be more helpful to focus on advising and coaching the charity’s management in learning valuable skills (such as writing a business plan), rather than doing it yourself; this will ensure that your contribution makes a lasting change, as the charity becomes increasingly independent of your support.

There is a balance to strike between committing resources to charitable causes during your lifetime and leaving money to charity in your will. ‘Giving whilst living’ allows you to see the difference your contribution is making and get actively involved in supporting the cause.

This may also provide for an opportunity to engage the wider family, particularly the next generation, with one’s personal donor journey. However, some people may like to be generous to charities but concerned about their own savings, in which case legacy giving may be more appropriate. Many also opt to do both, taking a planned giving approach, as they wish to see their commitment through and provide long-term support, which their families can also see through, either through a charitable trust or by deploying a gift in a will.

If you decide to give through a charitable foundation, one key decision is whether the foundation will exist in perpetuity, distributing the investment income and preserving capital, or whether you want it to ‘spend out’ over a fixed period.

When planning your giving strategy, it’s important to begin by focusing on your overall aims, and identifying what kind of giving will help you achieve those aims. Key factors include how you want to allocate your resources for yourself and your family over your lifetime and afterwards, how personally involved you want to be in decisions about giving, and what you want your money to achieve.

Giving time

Giving time and contributing personal expertise and competences alongside money can be a powerful way to make your giving more rewarding. It fosters a deeper connection with the cause, a detailed understanding of the challenges the organisation faces, and an opportunity to share in its achievements. For many charitable organisations, particularly smaller and underfunded organisations, the contribution of skilled volunteers is hugely valuable, and can sometimes have a greater impact than donations of money.

Giving time need not mean participating in an organisation’s regular volunteering programme. It could involve contributing professional legal or financial expertise, mentoring the charity’s senior staff, fundraising through your networks of contacts, or becoming a trustee.

The starting point for giving time is to consider in broad terms what you want to get out of your giving. This will help you assess whether you want to give time, how much you want to give, and in what capacity.

Lifetime giving

There are many different ways that giving during your lifetime can be carried out, but it is important to maximise the impact of your donations by giving tax effectively. See Giving Mechanisms for more on which charitable vehicle is most suitable for you, and Tax-Efficient Giving for giving tax effectively.

Legacy giving

Charitable bequests can form part of your estate planning. Bequests can be made to specific charities named in your will, which is a gratifying way to know that you have contributed to the long-term financial security of that organisation. Alternatively, you can also choose to set up a charitable foundation through which to channel donations both during your lifetime and afterwards. See Legacies for more on the specific ways of leaving money to charities in your will and the tax advantages of legacies.

By choosing to permanently endow a foundation, you can ensure you have a long-term impact on issues, and provide a secure resource for future generations to draw upon. It is particularly appropriate if you are passionate about problems you believe will be with us forever.

Giving in perpetuity can also provide a focus for family engagement across generations, encouraging family members to work collaboratively towards the ends established by the founder. Permanently endowed UK trusts and foundations are required by law to preserve their endowments, and in doing so to balance the needs of present and future beneficiaries. As founder, the challenge is to create a clear, flexible statement of your charitable intentions so your philanthropy can remain responsive to changing needs over time.

Spend-out or spend-down foundations

Spend-out foundations are established to spend down their capital over a fixed period. They differ from traditional foundations which exist in perpetuity, spending only the interest and preserving the original capital investment. Foundations which plan to spend capital have greater flexibility to increase giving in times of greater need, whereas those spending only investment income may have fewer resources during any economic downturns.

The spend-out model can be suitable for donors who want their money to be given in a high-impact and strategic way, remaining closely connected to their passions. It is also suitable for those donors who want to contribute their own particular skills or knowledge. Some founders recognise that it can be difficult to preserve their intentions across generations, and fear mission drift and a decline in passion for the cause if their funds are given in perpetuity. Others believe that future generations should generate their own philanthropy, and are concerned that family members will view distributing someone else’s money as an administrative burden rather than a passion.

Most spend-out trusts will establish a specific timeframe (ie, to be spent over the next twenty years, or within ten years after the founder’s death). But they can remain flexible and respond to events as they near the expected time to close. It is vital for spend-out foundations to be clear with grantees about their timescales and either help them prepare for the funding to cease, or build relationships with grantees in preparation for a large grant or endowment to be made in the final phase of spend out.

In general, one should be aware that giving remains an ongoing process in an always changing environment. Therefore, you need to have these reflections and conversation(s) long term.

It is important to allow for change – ‘as you may have changed in your lifetime, so will the world after your lifetime’. That explains the need to think about the way you set up your foundation. There should also be a mechanism in place to highlight the possible amount of unused income in Trusts – bad practice legacy advice is very pertinent here.

Foundations are not known for often spending out but in 2023, the Lankelly Chase Foundation announced that it was going to close in five years’ time and will be ‘redistributing its assets’ until then. The Board were very open that the current methods of philanthropic practices have created a lot of barriers, exclusions, inequities, discrepancies for foundations’ and trusts’ beneficiaries and wanted to shift their framework of giving to accommodate to some of the problems that philanthropy has actually created. In 2024, the Foyle Foundation announced it will be spending out its assets to close in 2025.

Choosing how to make your social investment

In order to start the journey as a social investor, much like with any other financial investment it is prudent to take advice, unless you are a sophisticated investor.

There are many intermediaries and funds, as well as some notable innovative new platforms and organisations that you can draw guidance from or consider joining as a member. Some larger, more recognisable names have also started to incorporate social investment into their products, like Schroeders and Aberdeen Investments.

Some also opt for a total-portfolio impact or mission-aligned investment approach and look to align their investments generally with a purposeful approach that ties into their philanthropic approach and their overall vision. Similarly, one might also intentionally invest funds that have been earmarked for philanthropic activity in aligned investments, e.g. investments with an environmental focus, that are also diverted to charities working in that space.

Here are some others to look at:

Big Society Capital

The Big Exchange

Resonance

Bridges Fund Management

Social Finance

Toniic

The Giin

LGT Group

Giving Structures

There are a number of options a philanthropist may choose from concerning structuring their giving. It is important to consult your professional advisors about the choice that is best for you.

Some of the choices are:

- Donor-advised fund (DAFs): this is a charitable giving vehicle administered by a group created to manage charitable donations on behalf of organisations, families, or individuals. Using it is easy and only requires the participant to open an account in the fund and deposit cash, securities, or other financial instruments. They surrender ownership of anything they put in the fund, but retain advisory privileges over how their account is invested and how it distributes money to charities.

- Dedicated account: a regular bank account, allowing the philanthropist to make donations without the need for a giving structure.

- Foundation/(charitable) trust: a private foundation is a non-profit organisation that is usually created via a single primary donation from an individual or a business and whose funds and programmes are managed by its own trustees or directors. As such, rather than funding its ongoing operations through periodic donations, a private foundation generates income by investing its initial donation, often disbursing the bulk of its investment income each year to desired charitable activities.

- Social investment intermediaries: funds or financial organisations that invest smaller amounts in a number of frontline social sector organisations, social enterprises and charities.

STAGE 3: SETTING GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Establish clear personal philanthropic and/or social investment objectives to clarify what you want to achieve with your giving. Make it enjoyable. Elaborate on suitable giving structures.

- What do you want to achieve both short and long term? Setting clear objectives will help you to work out what is important to you, and provide you with something to assess the success of your giving against.

- Giving becomes rewarding when it reflects your core values and lifetime experiences, allowing you to see, and truly understand, what you are accomplishing.

- There are different philosophies and types of philanthropy and ways to engage that can be generally distinguished, although most of them have overlaps in their strategic implementation and range from how you might choose the cause area to how deeply you engage with the beneficiaries.

Different Approaches to Philanthropic Giving

Values-based philanthropy

Prioritises donors’ values to help effectively channel donations.

Strategic philanthropy – predictive model

A clear goal is decided, and how to achievement it/impact is designed and implemented. The strategy is driven by evidence/data.

Effective altruism

Effective altruism is about answering one simple question: how can we use our resources to help others the most? It is an evidence-based and analytical approach to finding the very best causes to work on, as well as deploying your skills and other resources to do the most good you can.

Transformative philanthropy

Turns the power of money into creative and decision-making power for many; donors are part of the process in direct contact with the supported group.

Entrepreneurial/emergent philanthropy

Motivated by a desire to pioneer, disrupt, innovate and to make a significant difference. This approach combines elements of Venture philanthropy and the application of an emergent strategy. An emergent strategy accepts that a realised strategy emerges over time as initial intentions collide with, and accommodate to, a changing reality. The term “emergent” implies that an organisation is learning what works in practice.

Catalytic philanthropy

Catalyses/mobilises a campaign that achieves measurable impact and focuses on issues to resolve, not organisations to support.

Venture philanthropy

A high-engagement and long-term approach whereby an investor for impact supports a social purpose organisation (SPO) to help it maximise its social impact – providing funding and expertise.

Types or ways of deploying your philanthropy

Individual philanthropy

Philanthropy is a deeply personal venture, and through setting objectives, you will become clear about what you would like to achieve with your giving. This provides the starting point for working out how to make that vision come to fruition.

Your objectives should reflect what is important to you and what is motivating you to give, and can be broader than simply choosing a cause to support. For some, their main objective is to improve their local community, whilst for others it is about bringing together their wider family.

Clear objectives provide you with a set of priorities to help inform your decision-making, and enable you to look back and assess the impact and success of your giving.

Impact and rewards tend to be greater when your giving is relevant to your own life, such as when you are seeking to support something you really care about, which aligns with your personal value propositions. To inform your objectives, it is important to think about past experiences with your giving: What have you enjoyed? What have you found frustrating? What has held you back from giving more and what have you learnt most from?

Everyone has different objectives for their giving, and these goals can be:

- Charitable – supporting specific causes that reflect your personal beliefs, experience and passions (see Defining a Focus)

- Personal – such as using your time productively after the sale of a business or passing on family values to the younger generation (see Giving Time, and Family Philanthropy)

- Corporate - if you are thinking about your giving from a business perspective, you may have additional objectives, such as engaging your employees or strengthening the company brand (see Corporate Philanthropy)

Some donors find it useful to take this a step further and create a vision and mission statement setting out what they want to achieve. (see Mission and Vision).

Objectives will evolve, and even change considerably, particularly if you are setting objectives for the first time. This is good as it reflects what you are learning about issues, what works and what you find rewarding. So, remember that defining your objectives is an ongoing process and it is advisable to revisit your objectives on a regular basis (see Reviewing Objectives).

Once you have your objectives, you need to translate these into something practical and achievable that reflects your resources. Your objective may be to help ‘disadvantaged youth’ in your own city, but there will be a multitude of different ways to achieve that. What you focus on and how you achieve that will depend on a combination of your own beliefs (you may want to focus on tackling root causes rather than relieving symptoms, for example), your resources and your knowledge of what works best. This is laid out in the ‘Developing a Strategy’ stage of the framework. This is also applicable to social investing and you might wish to focus investments around particular areas, for example biodiversity, clean energy, food and agriculture or investing with a gender lens.

It is important to set objectives for your impact so that you know what you want to achieve and whether you are achieving it. But you can also set specific objectives for organisations that you support — milestones that you want them to reach with your funding (see Charity Impact Evaluation).

Family philanthropy

Giving as a family is a great way to strengthen family ties, achieve multi-generational learning and to share values and long-term giving goals among your family members.